Taking advantage of extraordinary advances in the study of ancient DNA, researchers from Fudan and Xiamen Universities in China completed a detailed facial reconstruction of a Chinese emperor who ruled nearly 1,500 years ago. The DNA sample used to create the amazingly lifelike image was extracted from the skeletal remains of an individual known simply as Emperor Wu, who came from China’s Northern Zhou dynasty and served as sovereign from 560 to 578 AD.

In a new article just published in the journal Current Biology, the archaeologists, anthropologists and genetic scientists involved in the facial reconstruction project introduce the results of their handiwork, which shows Emperor Wu as he would have looked in his mid-30s. This would have been his age at the time of his death, which according to the researchers was likely caused by the effects of a stroke.

As the longest serving ruler of the short-lived Northern Zhou dynasty (557 to 581), Emperor Wu was known primarily for his accomplishments as a military leader. He built a powerful army that he used to defeat the Northern Qi dynasty and unite the northern part of China under his dynasty’s authority The country as a whole was split into northern and southern sections at that time, so Wu only technically served as emperor over one half of China.

Rediscovering Emperor Wu

Emperor Wu belonged to an ethnic group identified as the Xianbei. These nomadic warrior people lived in what is now northern and northeastern China, and also occupied the lands of ancient Mongolia farther to the north.

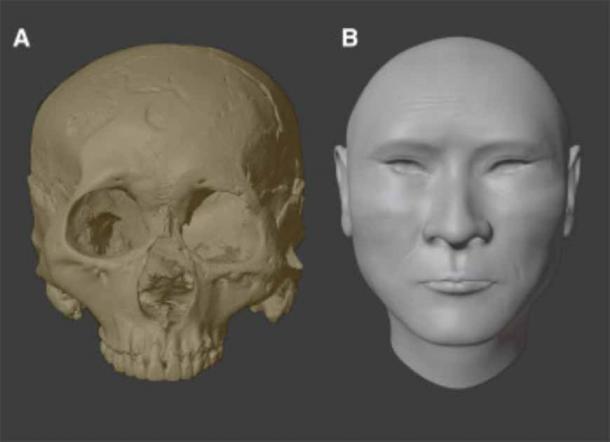

A: the highly detailed scan of the skull of Chinese Emperor Wu, and B the reconstructed facial features based on the skull and DNA extracted from it (Pianpian Wei / Current Biology)

However distinct his features might have been, there is no doubt that his appearance would have been representative for his ethnic type.

“Our work brought historical figures to life,” study co-author Pianpian Wei, an anthropological researcher from Fudan University in Shanghai, stated in a press release from Cell Press. “Previously, people had to rely on historical records or murals to picture what ancient people looked like. We are able to reveal the appearance of the Xianbei people directly.”

That accomplishment is especially notable in this case, because what was discovered was contrary to many experts’ expectations.

“Some scholars said the Xianbei had ‘exotic’ looks, such as thick beard, high nose bridge, and yellow hair,” explained study co-author Shaoqing Wen, an ancient DNA expert from Fudan University. “Our analysis shows Emperor Wu had typical East or Northeast Asian facial characteristics.”

Archaeologists discovered Emperor Wu’s remains during excavations in northwestern China in 1996. His bones were well-preserved inside his tomb, with his skull remaining almost completely intact.

In recent years improvements in ancient DNA extraction technology have enabled researchers to complete extensive genetic studies of long-deceased individuals, and in this case the Chinese researchers were able to collect more than one million genetic particles (referred to in scientific terms as ‘single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs) from the Emperor’s skeleton. As it turned out, these genetic samples contained a treasure trove of important and highly revealing information.

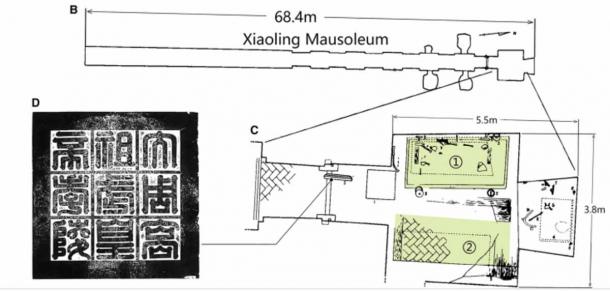

The Xiaoling Mausoleum where the Emperor was laid to rest, at position ‘1’. D is the Epitaph of Xiaoling (Pianpian Wei / Current Biology)

From the data obtained during their intensive DNA analysis, the researchers were able to determine the precise color of Emperor Wu’s skin, hair and eyes. Because his skull was so well-preserved it was possible to recreate a 3D image of Wu’s face and head that included these details, and what resulted was a vivid facial reconstruction of a man with brown eyes, thick black hair and dark-to-medium-colored skin. Despite belonging to a lost ethnic group, he looked very much like modern-day Asians born in the northern and eastern parts of the continent.

In addition to what they learned about Emperor Wu specifically, the researchers were able to reach some new conclusions about migration patterns in ancient China. While the DNA research confirmed that Wu had come from the Xianbei ethnic group, it also showed this group had interbred with the Han Chinese people who were living in northern China before the Xianbei arrived. At an earlier time the Xianbei had migrated south into China from Mongolia, their original homeland, and over time they blended in with the local population to create a new genetic mixture.

“This is an important piece of information for understanding how ancient people spread in Eurasia and how they integrated with local people,” Wen said.

The study of his skeletal remains as a whole showed that Emperor Wu died when he was just 36 years old. While many archaeologists believed he must have passed away as a result of an illness, others suggested he might have been poisoned to death by a political rival, which would have been a legitimate risk at that time in history.

Ater analyzing his DNA closely, Wen, Wei and their colleagues developed a different hypothesis altogether. Based on certain abnormalities in his genetic makeup, they believe the emperor may very well have died from the side effects of a stroke.

He was genetically predisposed to such an outcome, and interestingly enough historical records offer some support for the stroke hypothesis. In the press release the researchers note that Wu was described by contemporary observers as “having aphasia, drooping eyelids, and an abnormal gait—potential symptoms of a stroke.”

China’s Incredible Genetic History

Encouraged by their success in this project, the researchers plan to turn their attention next to the ancient residents of the city of Chang’an in northwestern China. Over the course of many centuries, this cosmopolitan city served as the capital for many Chinese empires. It also represented the easternmost outpost of the Silk Road, the 4,000-mile-long (6,400-kilometer-long) east-to-west trade route that connected buyers and sellers from across the Eurasian land mass from the second century BC through the 15th century AD.

Primarily for economic reasons, people came to Chang’an from all over Asia, and some may have arrived from as far away as northern Africa or southern Europe as well. By analyzing DNA extracted from ancient skeletal remains recovered from burials in Chang’an, the researchers hope to decipher what will undoubtedly be a complex genetic puzzle, one that will reveal how migration from elsewhere impacted the region’s fascinating social, cultural and biological histories.

Top image: Not quite like the painting: the reconstructed face of Chinese Emperor Wu using DNA extracted from his remains, and the portrait of Emperor Wudi in the Thirteen Emperors Scroll . Source: Pianpian Wei / Current Biology.

By Nathan Falde